In Kyoto, there is an area called “Shimabara,” near the Kyoto Station. In the area, there were high-class licensed prostitute* houses (okiya in Japanese) and party venues (ageya in Japanese) were gathered, called kagai in Japanese, in the Edo, Meiji, Taisho and early Showa periods.

High-class licensed prostitute*: A woman entertaining high-class guests in a feast, who was highly educated and was versatile in the arts, as well as who was beautiful and elegant (tayu in Japanese). The tayu is the supremacy of licensed prostitutes.

In old Japan, entertainment districts were classified into two kinds according to the business outline, kagai, as described above, and yukaku. The kagai is a place for social interaction and entertainment accompanied with cultural activities, and the yukaku is a house for sexual relationship. Shimabara belonged to the kagai, and the high-class kagai at that.

The okiya and ageya in Shimabara had the highest social status, because the gests were members of the Imperial Family, court nobles, high-rank samurai, and wealthy merchants. Further, in this area, not only parties but also literary activities including creations of tanka (Japanese poem of thirty-one syllable verse) and haiku (Japanese poem of seventeen syllable verse) were enthusiastically carried out, and in the middle of the Edo period, “Shimabara world of haiku” was established.

However, the limited transportation access and the high status being the cause, the flow of people moved to the central area of town such as Gion, and unfortunately only three historical buildings remain now.

Now, I’d like to explain the words okiya and ageya, described above, in more detail. The okiya means a house having the tayu and sending them according to the request of ageya or ochaya, in which the tayu lived and were educated. The ageya means a party venue, corresponding to, what is now called, a Japanese-style restaurant. In old Japan, the place where the tayu lived and the place the tayu worked were separated. The ageya requested the dispatch of the tayu to the okiya, and the Tayu went to the ageya from the okiya. The ochaya means a party venue similar to the ageya, but they didn’t have their own kitchen and cuisine was brought from an outside caterer.

First, one of the remaining three historical buildings in Shimabara is Shimabara Omon.

The entrance of the Shimabara district is the Shimabara Omon. The gate was built in 1867, and is a Korai-mon gate (we can often see it in castles and temples) with a gable roof made of clay tiles and having a width of about 1.82 meters. There is a big willow tree in front of the gate, which is generally called “Looming Back Willow”, and this scene has almost not been changed from the late Meiji period. A stone pavement extends from the gate, and in those times, 50 ageya shops and 20 okiya shops stood in an orderly line on the both sides of the pavement.

Wachigaiya

The Wachigaiya is the okiya, located northwest from the Omon, and it takes a few minutes on foot. The okiya holds tayu and continues the dispatching service and reception service even now.

The foundation of the Wachigaiya was in 1688. The shop first was run only as the okiya and concurrently was run as the ochaya later. The wooden two-storied building was built in 1857, and the present appearance appeared around 1871 after repeated extension works.

Entering the house, you will find a shop curtain and a glass door having the family crest of the Wachigaiya. This family crest attaches to an outside light on the roof, which makes its distinctive character. You also find traditional Japanese-style furniture including a hanging scroll in a wooden floor room. A big stairway is at the left-hand side in the room. The big stairway is a formal one and the house has other stairways in order to avoid customers bumping into each other.

Crossing the wooden floor room, you will go through an engawa (it looks like a corridor but is a passageway made between a Japanese-style tatami room (the inside) and a garden (the outside). The engawa bulges out from the edge of the room and is made of wood). You can see an inner court (West Court) on the left side, and shoji screens (paper sliding doors) of the main reception room. The engawa has no pillars because when customers look at the inner court, they can enjoy taking a long look at the court from the room without obstruction by pillars.

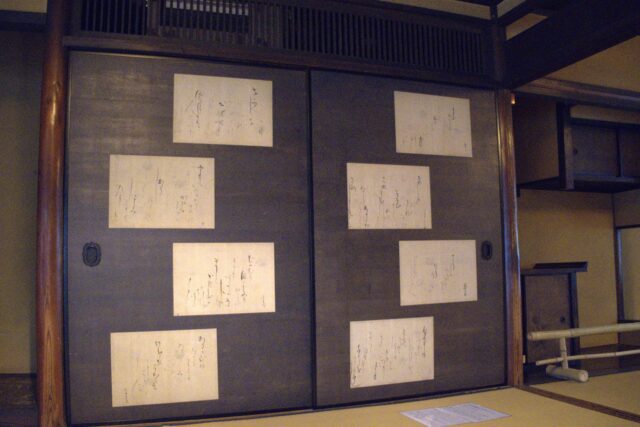

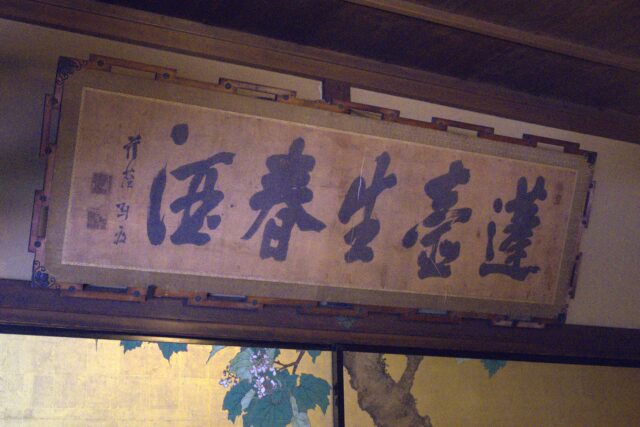

The main reception room is surrounded by glass-fitted shoji screens. In this reception room, there is a byobu (a Japanese traditional folding screen used to block the wind and prevent others from looking in) decorated with Kondo Isami’s own handwriting. In addition, strips of paper on which tanka or haiku is written are pasted, from which we can recognize that the creation the tanka or haiku enthusiastically once carried out. The room has another inner court, East Court.

As the Wachigaiya does business even now, usually we cannot see the inner part of the house. We can see it accompanied by explanations only at the time of the special opening.

Sumiya

The following big Japanese-style two-storied building having laterally continuous lattices is the ageya, Sumiya. This ageya building has a width of about 31.5 meters, and is designated as an important cultural property because it is the only one relic ageya building in Japan. It was built around 1787. The Sumiya stopped the party business in 1985, and now the building is open to the public as “Sumiya, Museum of Entertainment Culture.”

When looking at the shop curtain with the large family crest, moving forward, you see the main entrance at the right side and the kitchen door in front of you. You also can see a sword cut, made by someone of Shinsengumi (police and military force in the Edo-period) on a pillar of the building.

Kitchen

There is a large kitchen in which a cooking place and an about 91-square-meter tray service place. The kitchen has novel facilities so that you can’t think that the building was built in the Edo-period, such as barrier-free floor in order to reduce accidents as much as possible because many people worked in the dark, and basement storage.

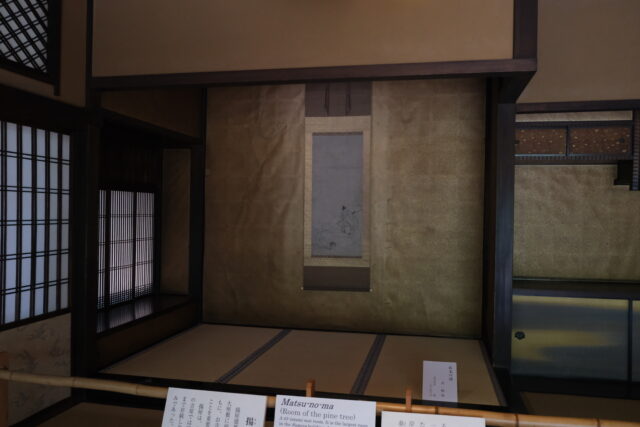

Matsu no Ma (Pine Tree Room)

The ageya has two reception rooms and each room has its own garden. This room is a big reception room having an area of 78 square meters (43 tatami mats), and has a garden in which big pine trees named Garyu no matsu (a big pine tree having a shape looking like a lying dragon) are planted. Once Garyu no matsu was formed by only one pine tree, but the pine tree died at the end of the Taisho-period and only the trunk remains now. The Garyu no matsu that we see now is formed by three pine trees (the second generation) to recreate the shape that seen in the Edo-period. The furniture, such as a hanging scroll in a tokonoma (a Japanese-style alcove) and images painted on fusuma (papered sliding doors to partition off rooms), are breathtakingly glorious with exquisite craftsmanship.

-

The glass in the shoji screen cannot be created now. The garden view seen through the glass is a little bit warped, which makes the view better atmospherically. There are many patterns made by frames of shoji screen, and they are all very Japanese patterns.

Ajiro no Ma (Wickerwork Room)

The room is the other reception room on the first floor having an area of 51 square meters (28 tatami mats), and wickerwork ceilings. The reception room has its own inner garden too.

In the reception room, it was dark even in daytime, and so in the Edo-period, the room was made bright using a large number of candles, resulting in deposition of a large amount of soot on the ceilings, walls, and other parts. Although the soot on the ceilings and walls could be somehow removed, unfortunately, the soot on the paintings on the fusuma could not be removed.

The combination of the patterns of frames of the shoji screens is also wonderful in this room, and soft light came into the room from the outside. The big reception room having 43 tatami mats is overwhelming, but the modest room having 28 tatami mats is affectionate.

What do you think about the traditional Japanses buildings as described above? The buildings are glorious and, at the same time, wistful and elegant. In particular, I admired the patterns made by the frames of the shoji screens. In addition, a material in some place was selected after deep thinking about the place and its use, for example, transparent glass was used in some place and frosted glass was used in the other place.

Although I had my attention caught only by appearances of buildings before, I’d like to shift my attention also to interior of buildings from this time forth.

Leave a Reply